Research Triangle Park, NC (Feb. 9, 2018) – Once light-rail cars are zipping along the 17.7-mile corridor between Durham and Chapel Hill in 2028, a 45-minute transit ride could get residents who live near Crest Street in Durham to 11,000 more jobs than they can reach in that amount of time today and those near East Lakewood at Memphis Street to 15,000 more.

Research Triangle Park, NC (Feb. 9, 2018) – Once light-rail cars are zipping along the 17.7-mile corridor between Durham and Chapel Hill in 2028, a 45-minute transit ride could get residents who live near Crest Street in Durham to 11,000 more jobs than they can reach in that amount of time today and those near East Lakewood at Memphis Street to 15,000 more.

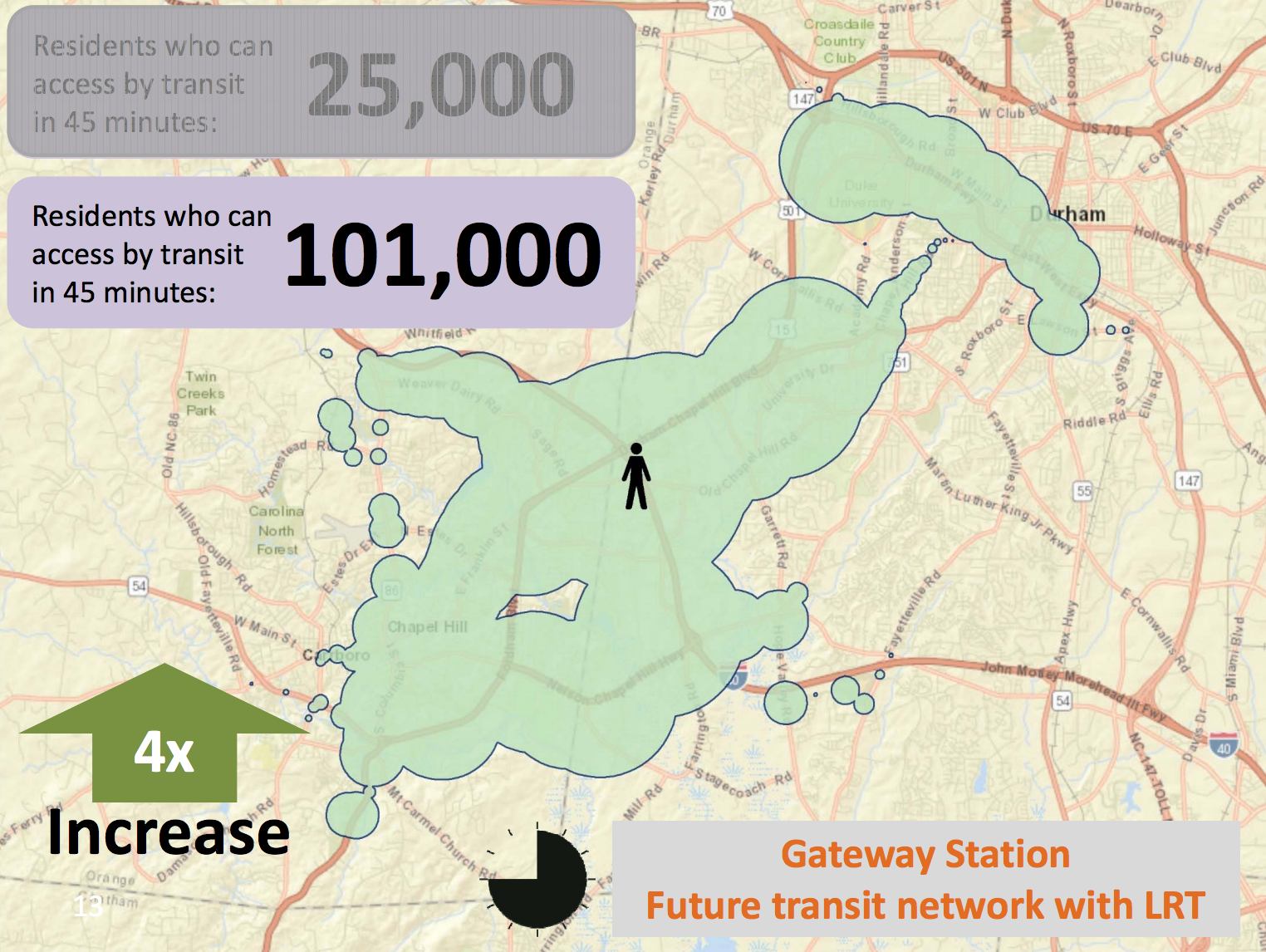

Duke Hospital North could have access to 90 percent more potential employees and the light rail’s Gateway Station area to 400 percent more.

And that’s based on today’s numbers of jobs and homes.

From 2018 to 2057, the project potentially could add $3.2 billion in property value and $1.4 billion in tax revenue as well, GoTriangle projections show.

As impressive as those numbers are, what will make the project extraordinary is finding ways to increase the number of people who get to share in the prosperity by using community goals to guide the growth around the line’s nearly 20 stations, Triangle leaders say.

That was the focus this week of the Connecting to Opportunity summit sponsored by GoTriangle, Triangle J Council of Governments and Gateway Planning. The event at the Durham Performing Arts Center brought together national experts, local elected officials, business owners, developers, transit planners and community members to explore how to ensure there is room for everyone along the light-rail line.

“This is a huge opportunity to not waste,” said Meea Kang, a developer who has been spearheading affordable housing projects in California for more than 20 years. “The region can’t afford not to build the housing or the infrastructure and then to make sure it’s sustainable and resilient. I love to disrupt. The light rail is a disruption, and that’s when innovation happens.”

Among the innovative housing ideas presented at the summit were allowing Accessory Dwelling Units (granny flats and mother-in-law suites), encouraging homeowners to build garage apartments and to divide their too-large homes and creating more affordable and sustainable micro-housing.

Given the 67 people a day that Wake County is adding and the 20 people a day in Orange and Durham counties, the Triangle can’t keep building housing the way it has been over the past decades even if it wanted to.

“You’d have to add the entire acreage of Durham, all 73,000 acres, to house the people coming in,” said Peter French, CEO of Rising Barn, a builder of sustainable small homes in San Antonio, Texas. “You’re probably not going to find that.”

‘A catalytic, transformative project’

Regardless of the strength of any other metrics, without affordable housing incorporated into the development along the light-rail line, the project can’t be considered successful, several summit speakers said. Too many other U.S. regions have tried to address surging land and housing prices around new transit lines when it’s too late to keep from leaving some people behind. Charlotte, for example, has found there is too little affordable housing along its Blue Line light-rail system.

Regardless of the strength of any other metrics, without affordable housing incorporated into the development along the light-rail line, the project can’t be considered successful, several summit speakers said. Too many other U.S. regions have tried to address surging land and housing prices around new transit lines when it’s too late to keep from leaving some people behind. Charlotte, for example, has found there is too little affordable housing along its Blue Line light-rail system.

“We know this is a catalytic, transformative project for our region,” said Wendy Jacobs, chairman of the Durham County Board of Commissioners and a member of the GoTriangle Board of Trustees. “It’s also a critical project to help us address a lot of existing inequities we have in our communities. We still have 24 percent of children living in poverty in Durham. Unemployment is very high in certain census tracts. Being able to connect more people in our community to more job opportunities is really critical.”

Making sure it’s not just the wealthy living in the walkable, vibrant and mixed-use communities planned for many of the light-rail stations will require acting deliberately to be inclusive, creating many private-public partnerships, passing new municipal policies and regulations, looking at housing for lower income workers as public infrastructure and forging a shared regional vision, speakers said.

“We understand our futures are inextricably linked, that our fates are sealed together,” Jacobs said of Durham, Orange and Wake counties. “We must come up with, from the get-go, an agreed upon shared strategy and plan that we all understand, the private sector and the public sector, with the shared goals for each station area, the expectation that they will have this amount of affordable housing. There needs to be shared buy-in from the beginning.”

There also needs to be a willingness to change the rules.

“Everything we proposed was illegal,” Kang said about an affordable housing project she built in Sacramento that required 16 special variances.

The allowable density was 30 units per acre. She built 72 per acre. Required parking was 2.5 spaces per unit. She built one per unit.

Today, the project, which stands on the site of an old gas station that Kang had to clean up, has transformed a dying neighborhood. More than 40 percent of the residents walk, bike or take transit to work.

Being proactive on policies

In Chapel Hill, leaders already are looking at ways to rewrite ordinances to eliminate barriers to affordable housing, said Loryn Clark, the town’s executive director of the Office of Housing and Community.

In Chapel Hill, leaders already are looking at ways to rewrite ordinances to eliminate barriers to affordable housing, said Loryn Clark, the town’s executive director of the Office of Housing and Community.

“The other piece is collaboration,” she said. “We collaborate with local government partners to look at issues more comprehensively than we have in the past. We used to come up with our own plans and strategies individually. Now we’re collaborating with Carrboro, Hillsborough and Orange County to share resources and ideas.”

Having the right zoning ordinances in place also will be critical to easing more affordable or inventive housing through the political process, said Karen Lado, an affordable housing consultant in Durham

“If you put the elected [officials] in positions of having to vote on every project, it’s death by 1,000 cuts,” she said. “Think about how you have these policy debates at the level of land use, when you really can frame them in terms of what kind of community do we want to be? It brings different voices into the conversation and allows you to think about the longer term vision.”

Some alternatives to traditional housing that might require rule changes were highlighted by French of Rising Barn and Jonathan Coppage, a researcher in urbanism with the R Street Institute and a former editor at American Conservative.

Coppage says governments should help existing homeowners build garage apartments, divide their homes into duplexes or add granny flats. Once Portland started waiving permit fees for these types of construction, the Oregon city added 1,000 more affordable units to its housing stock.

“Unlike almost every other mode of development, ADUs are not primarily put up by big developers,” Coppage said. “Very often they are built by homeowners, by the people with a stake in their community. It’s an investment people are making in their own neighborhoods.”

French’s company has built communities of small, sustainable and affordable homes and used some as small as 200 square feet to infill existing neighborhoods.

“Chapel Hill is 95 percent built up,” he said. “Think about what that means.”

His well-built, movable homes often sit on a slab in a backyard, so no new streets or other such infrastructure is required.

“This is the Research Triangle,” he said. “You have a robust startup community. Find a way to engage people to be part of the solution. There is a lot of opportunity there.”

And there’s the cost

Paying for affordable housing can take some creative solutions, some summit speakers said. Among the ideas offered were designating some tax revenue to it, offering density credits for developers and creating private-public philanthropy funds, maybe tied to area universities, to offer revolving loans.

Paying for affordable housing can take some creative solutions, some summit speakers said. Among the ideas offered were designating some tax revenue to it, offering density credits for developers and creating private-public philanthropy funds, maybe tied to area universities, to offer revolving loans.

“We have 2 cents on the tax rate in Durham for affordable housing,” said Durham Mayor Steve Schewel, a member of GoTriangle’s Board of Trustees. “If you have a $200,000 house in Durham, you pay $40 a year to help build a house for someone else. Know how many people I've heard complain about that? Zero.”

The phrase “a rising tide lifts all boats” cropped up more than once at the Connecting to Opportunity summit, and Andre Pettigrew, director of Durham’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development, put that into perspective:

“That works really well if you have a boat,” he said “If you don’t have a boat and you can’t swim, you might drown.”

And that’s the power of the public’s investment in transit systems, according to French of Rising Barn.

“The bus (or train) is the boat,” he said. “It gives you mobility, and mobility gives you freedom.”

About the summit

Plans for the Connecting to Opportunity summit were included in the application that GoTriangle, in partnership with Durham city and county, Chapel Hill and TJCOG, filed seeking a $1.6 million federal grant specifically for transit-oriented development planning. The grant was awarded in 2016.

The idea of transit-oriented development is to vastly reduce the need for driving by using train stations as “town centers” for creating dense, pedestrian-oriented communities that include offices, homes, retail space, parks, grocery stores and restaurants. Plans usually also call for bicycle-friendly streets and easy connections to bus routes.

Find the presentations from the summit at gotriangle.org/connectingopportunity. For a compilation of tweets from the event, see the post from Orange Politics at bit.ly/summittweets.